The analysis of the crime data in Austria for the year 2021, focusing on NUTS 3 regions, with the data sourced from Eurostat.

Data Preprocessing

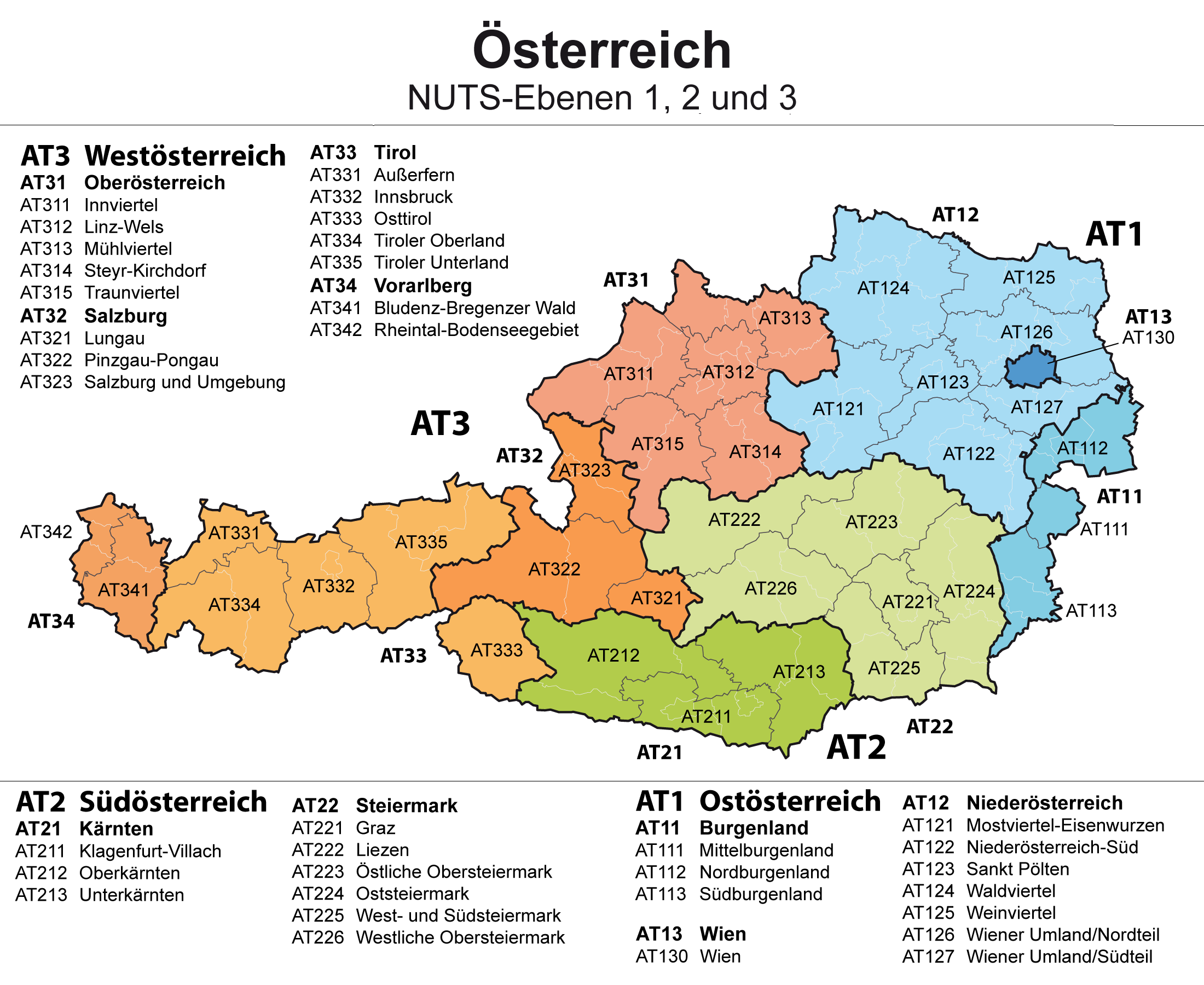

We will focus on the Austrian regions according to the NUTS 3 administrative division.

# Load necessary libraries

library(eurostat)

library(ggplot2)

library(psych)

id = 'crim_gen_reg'

crim_data = get_eurostat(id=id)

# Filter for data from the year 2021

data_2021 = subset(crim_data, format(TIME_PERIOD, '%Y') == '2021')

# Filter for Austrian NUTS 3 regions

at_data = data_2021[grepl('^AT[0-9]{3}$', data_2021$geo), ]

df = subset(at_data, select = c(unit, iccs, geo, values))

df = label_eurostat(df)

# The subcategories 'Burglary of private residential premises' and

# 'Theft of a motorized land vehicle' are already included in 'Burglary' and 'Theft'.

# We will exclude them to avoid duplication.

df = subset(df, !(iccs %in% c('Burglary of private residential premises',

'Theft of a motorized land vehicle')))

# Separate data into absolute numbers and per 100k inhabitants

nr_df = subset(df, df$unit == 'Number', select = c(iccs, geo, values))

pht_df = subset(df, df$unit == 'Per hundred thousand inhabitants', select = c(iccs, geo, values))

# Aggregate data by crime category (iccs) and region (geo)

nr_iccs_df = aggregate(list(values = nr_df$values), list(iccs = nr_df$iccs), sum)

nr_geo_df = aggregate(list(values = nr_df$values), list(geo = nr_df$geo), sum)

pht_iccs_df = aggregate(list(values = pht_df$values), list(iccs = pht_df$iccs), mean)

pht_geo_df = aggregate(list(values = pht_df$values), list(geo = pht_df$geo), mean)

Initial Data Exploration

We will analyze the number of criminal offenses in the regions of Austria according to the NUTS 3 administrative division for the year 2021.

At the NUTS 3 level, the territorial units of Austria are divided into so-called groups of political districts (Gruppen von Politischen Bezirken). The territorial division is shown on the following map.

Categories of Criminal Offenses

From 2008 onwards, the statistics include police-recorded offences for homicide, assault, sexual violence, robbery, burglary, (of which) burglary of residential premises, theft, (of which) theft of motorized land vehicle. [src]

rows = nr_iccs_df[order(-nr_iccs_df$values),]

row.names(rows) = 1:5

rows

theme_set(theme_gray(base_size = 14))

options(repr.plot.width=14, repr.plot.height=6)

ggplot(nr_iccs_df, aes(x=reorder(iccs, values), y=values)) + ggtitle('Categories of criminal offences') +

geom_bar(stat='identity') + ylab('count') +

geom_text(aes(label=values), hjust=-0.3) +

coord_flip() + theme(axis.title.y = element_blank()) +

expand_limits(y = c(0, 75000))

ggplot(pht_df, aes(x=reorder(iccs, values), y=values, fill=iccs)) +

geom_boxplot(outlier.color='red', show.legend=F) + ylab('relative count [per 10^5 inh.]') +

coord_flip() + theme(axis.title.y = element_blank()) +

geom_jitter(color='black', size=0.1, alpha=0.8, show.legend=F)

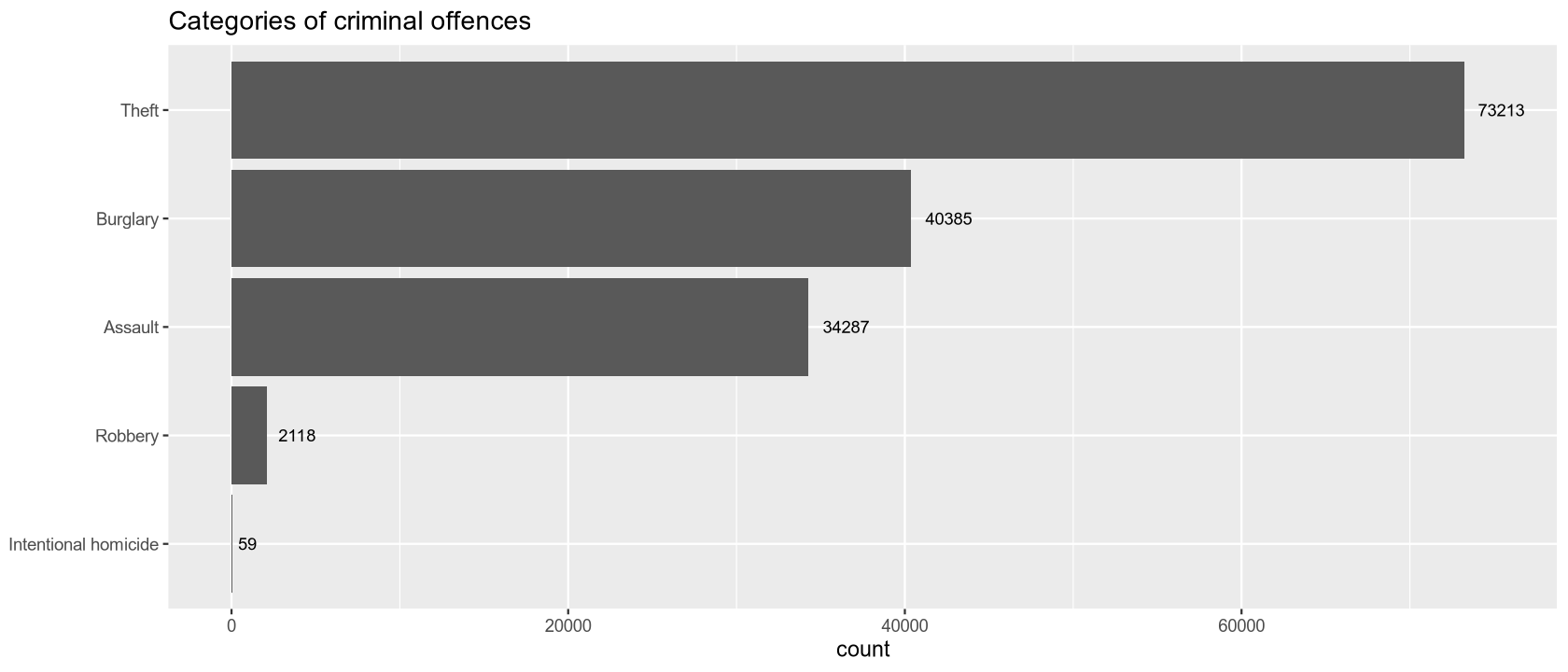

| iccs | values | |

|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | |

| 1 | Theft | 73213 |

| 2 | Burglary | 40385 |

| 3 | Assault | 34287 |

| 4 | Robbery | 2118 |

| 5 | Intentional homicide | 59 |

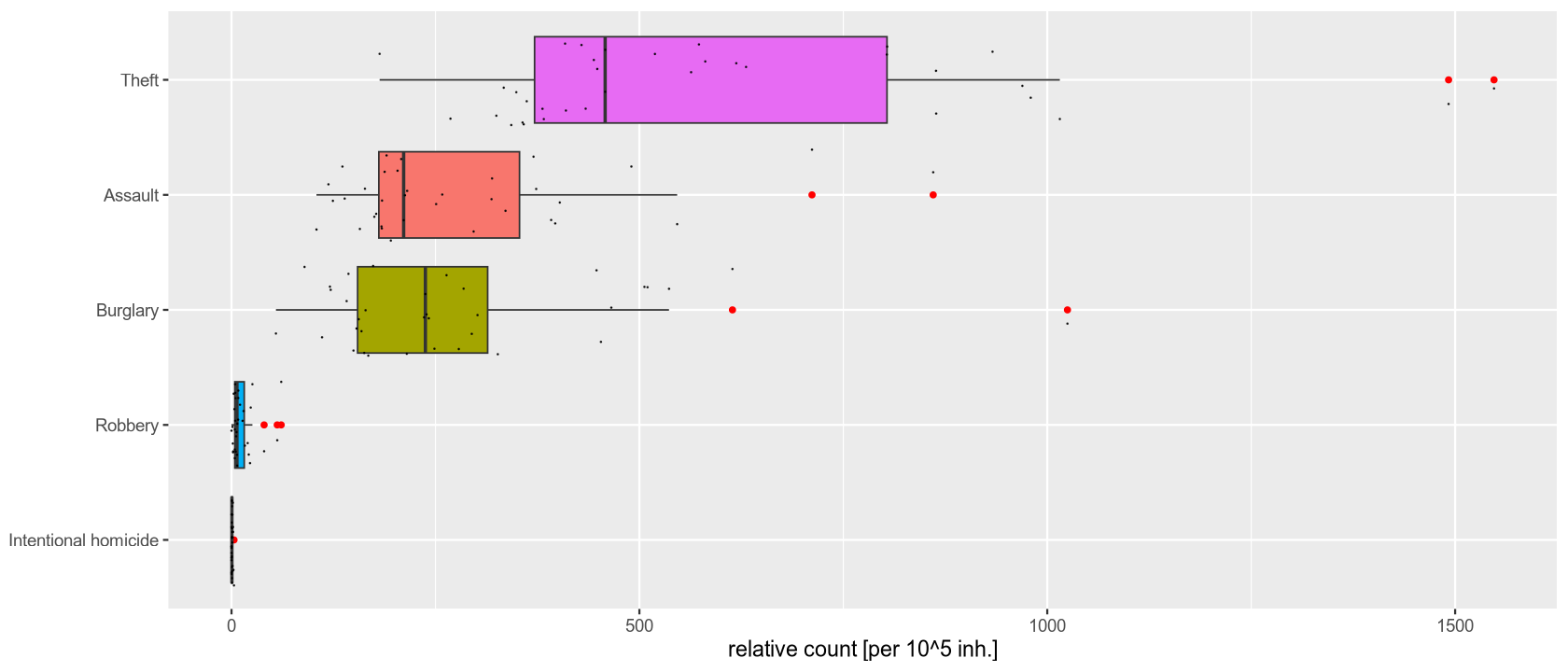

The table and the cumulative frequency chart show that in 2021, the most common category of crime was theft (a total of 73,213 cases), and the least common was intentional homicide (a total of 59 cases). The second graph (a boxplot of relative frequencies per 100,000 inhabitants) also shows that for more frequent crimes, the relative values vary significantly depending on the region. Specifically for theft, we observe two outlier values, which in this case are Wien and Linz-Wels.

Regions by NUTS 3 Division

rows = merge(x = nr_geo_df, y = pht_geo_df, by = 'geo')

rows = rows[order(-rows$values.x),]

colnames(rows) <- c('geo', 'count', 'relative.count')

row.names(rows) = 1:35

cat('Top 5')

head(rows, 5)

cat('Bottom 5')

tail(rows, 5)

summary(nr_geo_df)

r = describe(nr_geo_df$values, skew=F, IQR=T, ranges=F)

rownames(r) = c('values')

r$var = c(var(nr_geo_df$values))

r[,c(2,4,7,6)]

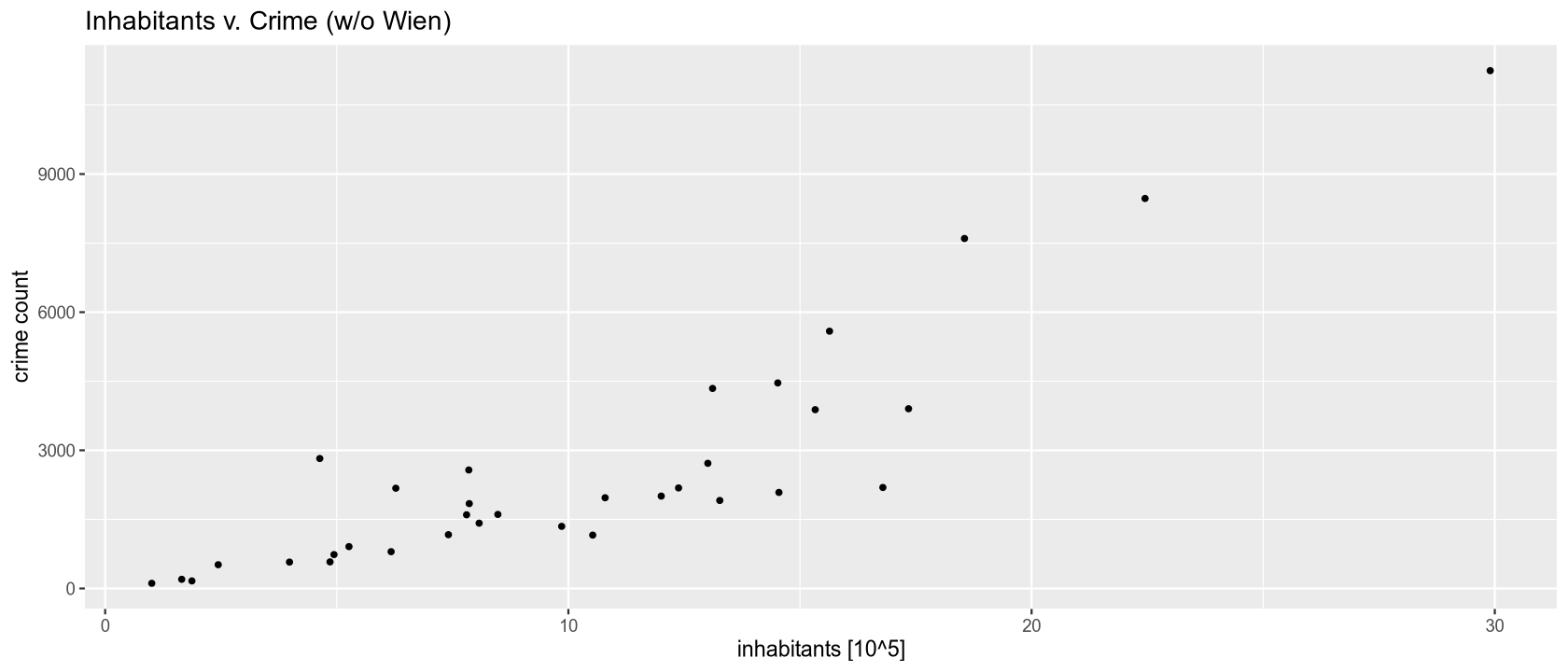

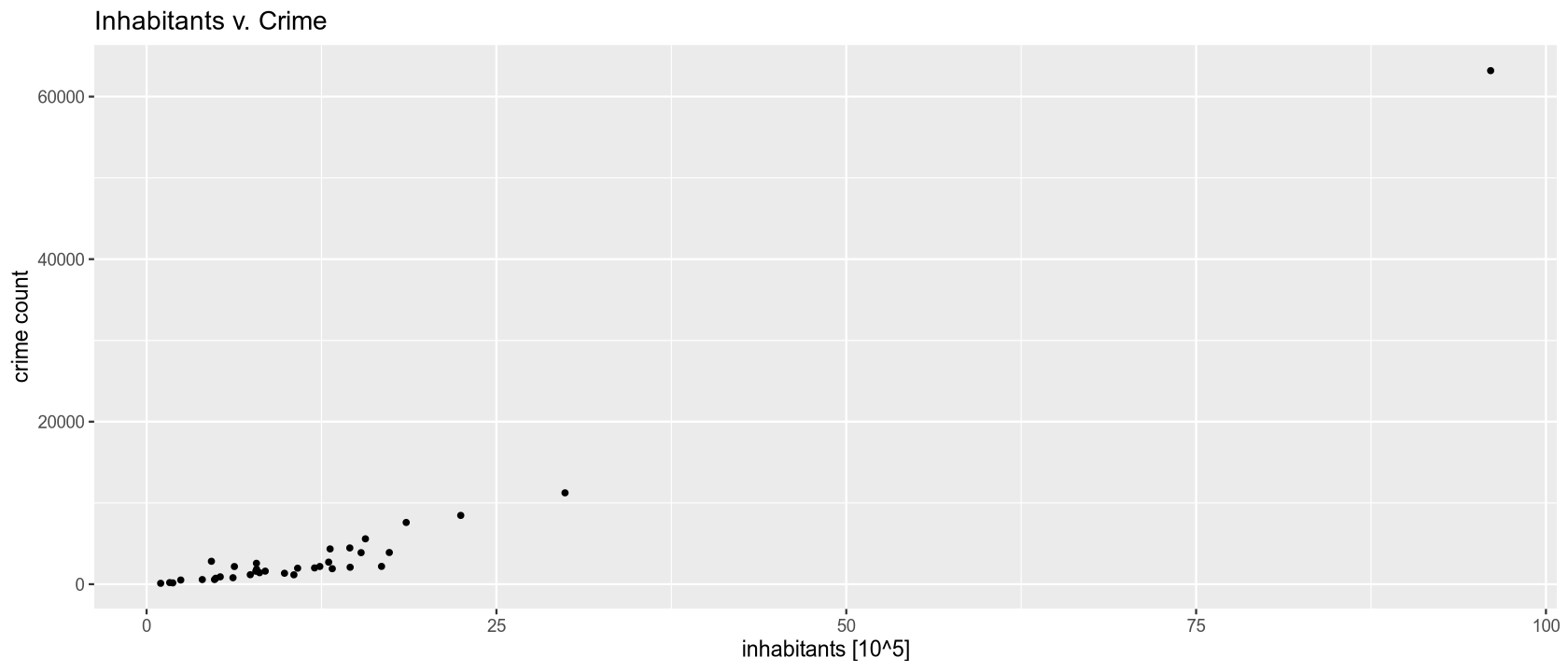

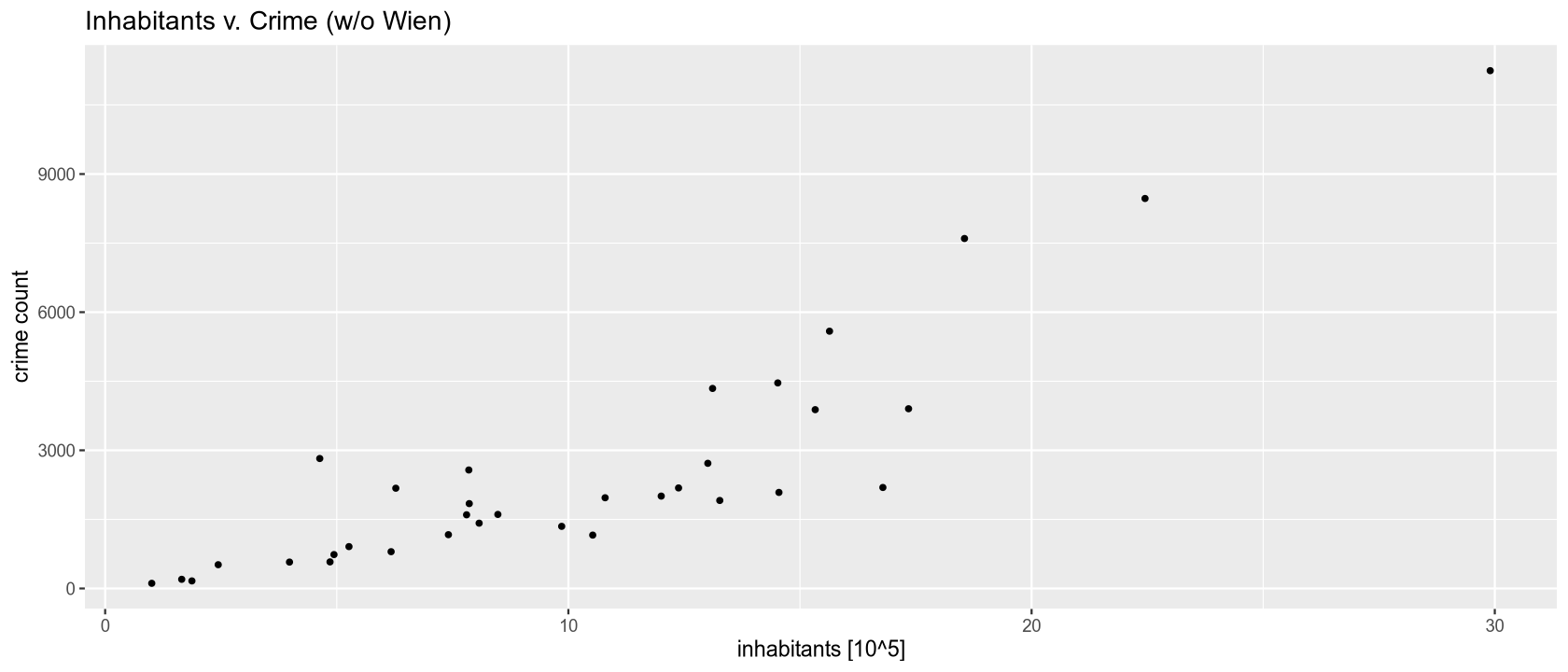

ggplot(rows, aes(x=count/relative.count, y=count)) + geom_point() + ggtitle('Inhabitants v. Crime') +

xlab('inhabitants [10^5]') + ylab('crime count')

ggplot(rows[rows$geo != 'Wien', ], aes(x=count/relative.count, y=count)) + geom_point() + ggtitle('Inhabitants v. Crime (w/o Wien)') +

xlab('inhabitants [10^5]') + ylab('crime count')

Top 5

| geo | count | relative.count | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | |

| 1 | Wien | 63198 | 657.988 |

| 2 | Linz-Wels | 11245 | 376.068 |

| 3 | Graz | 8469 | 377.248 |

| 4 | Salzburg und Umgebung | 7600 | 409.668 |

| 5 | Innsbruck | 5587 | 357.274 |

Bottom 5

| geo | count | relative.count | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | |

| 31 | Liezen | 573 | 143.986 |

| 32 | Osttirol | 516 | 211.416 |

| 33 | Außerfern | 199 | 120.410 |

| 34 | Mittelburgenland | 164 | 87.576 |

| 35 | Lungau | 112 | 111.344 |

geo values

Length:35 Min. : 112

Class :character 1st Qu.: 1034

Mode :character Median : 1970

Mean : 4287

3rd Qu.: 3352

Max. :63198

| n | sd | var | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | |

| values | 35 | 10540.04 | 111092439 | 2318.5 |

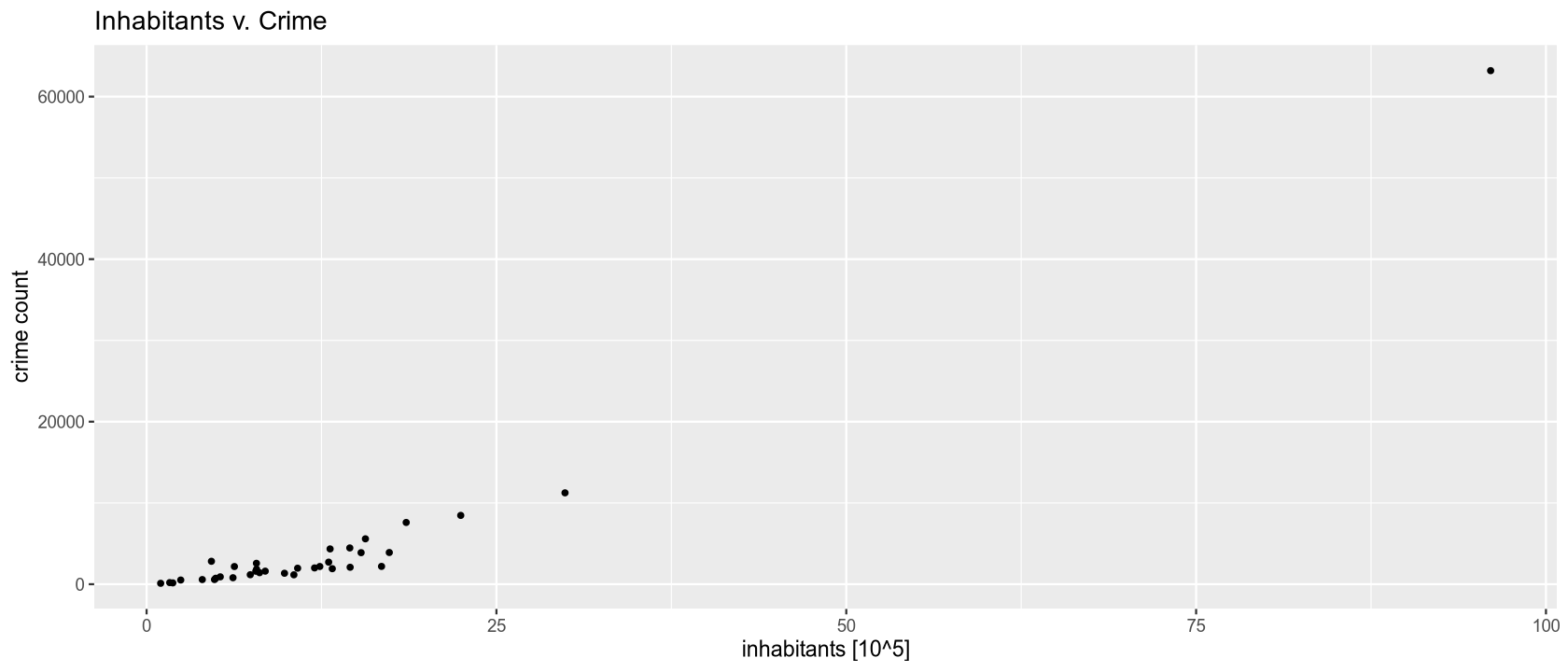

The table shows that the areas with the highest crime counts are Wien (63,198), Linz-Wels (11,245), and Graz (8,469), which contain Austria’s largest cities. The fewest crimes are recorded in smaller regions with smaller populations: Mittelburgenland (164) and Lungau (112). The graphs also show that regions with larger populations have a higher frequency of recorded crimes.

rows = merge(x = nr_geo_df, y = pht_geo_df, by = 'geo')

rows = rows[order(-rows$values.y),]

colnames(rows) <- c('geo', 'count', 'relative.count')

row.names(rows) = 1:35

head(rows, 5)

options(repr.plot.height=6)

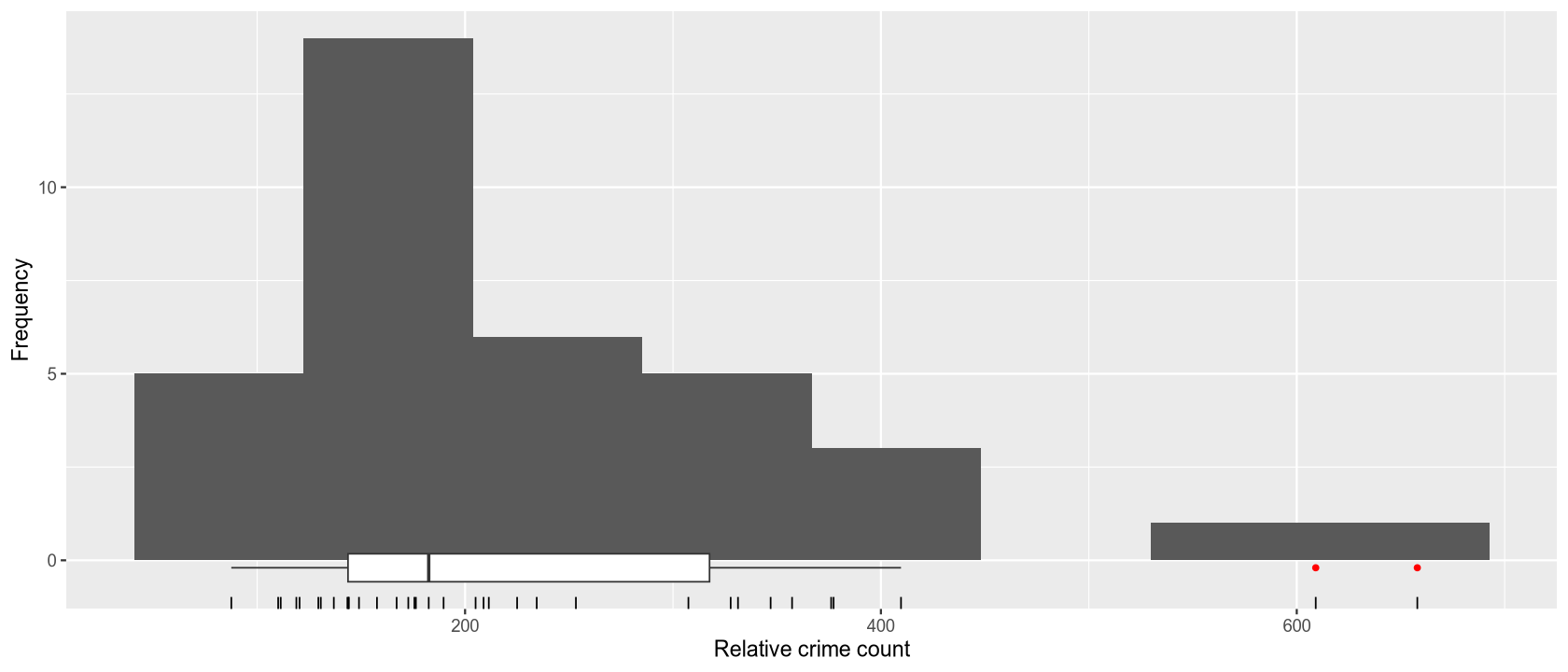

ggplot(pht_geo_df, aes(x=values)) +

geom_histogram(bins=8) + xlab('Relative crime count') + ylab('Frequency') +

geom_rug(aes(values, y = NULL), length = unit(0.02, "npc")) +

geom_boxplot(outlier.color='red', show.legend=F, position = position_nudge(y = -0.2))

| geo | count | relative.count | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | |

| 1 | Wien | 63198 | 657.988 |

| 2 | Bludenz-Bregenzer Wald | 2822 | 609.134 |

| 3 | Salzburg und Umgebung | 7600 | 409.668 |

| 4 | Graz | 8469 | 377.248 |

| 5 | Linz-Wels | 11245 | 376.068 |

The histogram of relative crime frequencies shows the approximate distribution of observed values across all categories and regions. Interesting data points are the regions Bludenz-Bregenzer Wald and Salzburg und Umgebung, which, despite having a relatively low absolute number of crimes, have a high relative frequency, ranking second and third after Vienna.

Analyzing the Relationship Between Region and Crime Type

ct = xtabs(formula=values ~ geo + iccs, data=nr_df)

addmargins(ct)

| Assault | Burglary | Intentional homicide | Robbery | Theft | Sum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Außerfern | 52 | 18 | 1 | 2 | 126 | 199 |

| Bludenz-Bregenzer Wald | 797 | 569 | 1 | 21 | 1434 | 2822 |

| Graz | 1807 | 2009 | 5 | 89 | 4559 | 8469 |

| Innsbruck | 1533 | 921 | 3 | 66 | 3064 | 5587 |

| Innviertel | 553 | 478 | 0 | 13 | 1042 | 2086 |

| Klagenfurt-Villach | 1138 | 948 | 2 | 43 | 2333 | 4464 |

| Liezen | 162 | 122 | 0 | 1 | 288 | 573 |

| Linz-Wels | 2373 | 3050 | 4 | 239 | 5579 | 11245 |

| Lungau | 25 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 112 |

| Mittelburgenland | 39 | 56 | 0 | 1 | 68 | 164 |

| Mostviertel-Eisenwurzen | 439 | 592 | 1 | 17 | 1134 | 2183 |

| Mühlviertel | 292 | 297 | 1 | 4 | 565 | 1159 |

| Niederösterreich-Süd | 971 | 1221 | 1 | 43 | 2108 | 4344 |

| Nordburgenland | 303 | 381 | 2 | 8 | 724 | 1418 |

| Oberkärnten | 227 | 137 | 2 | 2 | 431 | 799 |

| Östliche Obersteiermark | 528 | 391 | 0 | 11 | 913 | 1843 |

| Oststeiermark | 434 | 445 | 1 | 15 | 1016 | 1911 |

| Osttirol | 103 | 136 | 0 | 2 | 275 | 516 |

| Pinzgau-Pongau | 438 | 403 | 0 | 14 | 753 | 1608 |

| Rheintal-Bodenseegebiet | 1145 | 808 | 1 | 32 | 1897 | 3883 |

| Salzburg und Umgebung | 2027 | 1878 | 3 | 95 | 3597 | 7600 |

| Sankt Pölten | 466 | 711 | 3 | 37 | 1356 | 2573 |

| Steyr-Kirchdorf | 336 | 444 | 2 | 8 | 810 | 1600 |

| Südburgenland | 132 | 118 | 1 | 2 | 324 | 577 |

| Tiroler Oberland | 264 | 127 | 2 | 59 | 457 | 909 |

| Tiroler Unterland | 831 | 373 | 2 | 21 | 1491 | 2718 |

| Traunviertel | 443 | 516 | 1 | 16 | 1030 | 2006 |

| Unterkärnten | 315 | 241 | 0 | 6 | 606 | 1168 |

| Waldviertel | 449 | 522 | 0 | 10 | 989 | 1970 |

| Weinviertel | 400 | 673 | 3 | 17 | 1084 | 2177 |

| West- und Südsteiermark | 385 | 314 | 1 | 9 | 640 | 1349 |

| Westliche Obersteiermark | 173 | 154 | 0 | 4 | 405 | 736 |

| Wien | 13669 | 19685 | 14 | 1170 | 28660 | 63198 |

| Wiener Umland/Nordteil | 399 | 583 | 1 | 12 | 1198 | 2193 |

| Wiener Umland/Südteil | 639 | 1046 | 1 | 29 | 2188 | 3903 |

| Sum | 34287 | 40385 | 59 | 2118 | 73213 | 150062 |

The values in the contingency table are consistent with previous observations. High values are registered in populated regions and for common crimes. At first glance, the distribution of crime categories appears to be similar across all regions. We will now test this hypothesis.

Fisher’s Exact Test

We will use Fisher’s Exact Test to verify whether the probabilities of crime categories depend on the region, at a 5% significance level. This test can handle zero values in some cells and is suitable for larger contingency tables.

\(H_0\): Each row (region) is a realization of the same distribution (crime category), i.e., \(p_{ij} = p_{i:} \cdot p_{:j}\) for \(i=1,\ldots,35\) and \(j=1,\ldots, 5\).

\(H_A\): \(H_0\) is not true.

fish = fisher.test(ct, simulate.p.value = TRUE)

fish

Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data with simulated p-value (based on

2000 replicates)

data: ct

p-value = 0.0004998

alternative hypothesis: two.sided

At a 5% significance level, we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative, which states that the records of crime categories are not realizations of the same distribution. This means the probabilities of individual crime categories are different for different regions.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1: Correlation Between Population and Crime Count

ggplot(rows, aes(x=count/relative.count, y=count)) + geom_point() + ggtitle('Inhabitants v. Crime') +

xlab('inhabitants [10^5]') + ylab('crime count')

ggplot(rows[rows$geo != 'Wien', ], aes(x=count/relative.count, y=count)) + geom_point() + ggtitle('Inhabitants v. Crime (w/o Wien)') +

xlab('inhabitants [10^5]') + ylab('crime count')

During the initial data exploration, we observed that regions with a larger population have a higher frequency of recorded criminal offenses. We will now test this hypothesis at a 5% significance level using a non-parametric correlation coefficient test - Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

\(H_0 :\) There is zero correlation between the number of inhabitants and the frequency of crime in a region: \(\rho_S = 0\)

\(H_A :\) There is a positive correlation between the number of inhabitants and the frequency of crime in a region: \(\rho_S \> 0\)

x = rows$count/rows$relative.count

y = rows$count

round(cor(x, y, method='spearman'), 4)

cor.test(x, y, method='spearman', alternative='greater')

0.8641

Spearman's rank correlation rho

data: x and y

S = 970, p-value = 1.586e-08

alternative hypothesis: true rho is greater than 0

sample estimates:

rho

0.8641457

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient value of 0.86 indicates a very strong positive correlation. At a 5% significance level, we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative that there is a positive correlation between the number of inhabitants and the number of criminal offenses. The more populous a region is, the more crimes are recorded in that area.

Hypothesis 2: Comparing Homicide Rates in Austria and Slovakia

cd = crim_data[grepl('^AT[0-9]{3}$', crim_data$geo), ]

cd = label_eurostat(cd, fix_duplicated = TRUE)

cd = subset(cd, unit == 'Number')

cd = subset(cd, freq == 'Annual')

cd = subset(cd, iccs == 'Intentional homicide')

cd = aggregate(list(values = cd$values), list(TIME_PERIOD = cd$TIME_PERIOD), sum)

mean.AT = mean(cd$values)

median.AT = median(cd$values)

colnames(cd) = c('year', 'AT')

cd.AT = cd

cd = crim_data[grepl('^SK[0-9]{3}$', crim_data$geo), ]

cd = label_eurostat(cd, fix_duplicated = TRUE)

cd = subset(cd, unit == 'Number')

cd = subset(cd, freq == 'Annual')

cd = subset(cd, iccs == 'Intentional homicide')

cd = aggregate(list(values = cd$values), list(TIME_PERIOD = cd$TIME_PERIOD), sum)

mean.SK= mean(cd$values)

median.SK= median(cd$values)

colnames(cd) = c('year', 'SK')

cd.SK = cd

cd.AT$SK = cd.SK$SK

cd = cd.AT

cd

cat('AT mean, median: ', mean.AT, ',', median.AT, '\n')

cat('SK mean, median: ', mean.SK, ',', median.SK)

| year | AT | SK |

|---|---|---|

| <date> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| 2008-01-01 | 58 | 94 |

| 2009-01-01 | 51 | 84 |

| 2010-01-01 | 59 | 87 |

| 2011-01-01 | 82 | 96 |

| 2012-01-01 | 88 | 75 |

| 2013-01-01 | 62 | 78 |

| 2014-01-01 | 40 | 72 |

| 2015-01-01 | 42 | 48 |

| 2016-01-01 | 49 | 59 |

| 2017-01-01 | 61 | 79 |

| 2018-01-01 | 73 | 67 |

| 2019-01-01 | 74 | 76 |

| 2020-01-01 | 54 | 63 |

| 2021-01-01 | 59 | 55 |

AT mean, median: 60.85714 , 59

SK mean, median: 73.78571 , 75.5

We observe that the sample median number of homicides for the period 2008 to 2021 is 59 in Austria and 75.5 in Slovakia. We want to test at a 5% significance level whether the homicide rate in Austria is the same or significantly lower. We choose the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, which does not require data normality. Let \(\tilde{\mu}*\text{AT}\) and \(\tilde{\mu}*\text{SK}\) be the true respective median values.

\(H_0: \tilde{\mu}*\text{AT} = \tilde{\mu}*\text{SK}\)

\(H_A: \tilde{\mu}*\text{AT} < \tilde{\mu}*\text{SK}\)

wilcox.test(cd$AT, cd$SK, alternative='less', exact=F)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: cd$AT and cd$SK

W = 50, p-value = 0.01449

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is less than 0

At a 5% significance level, we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative, that the median frequency of homicides in Slovakia is significantly higher than in Austria.

Hypothesis 3: Normality of Homicide Data in Vienna

cd = crim_data

cd = subset(cd, unit == 'NR')

cd = subset(cd, freq == 'A')

cd = subset(cd, geo == 'AT13')

cd = label_eurostat(cd)

cd = subset(cd, iccs == 'Intentional homicide')

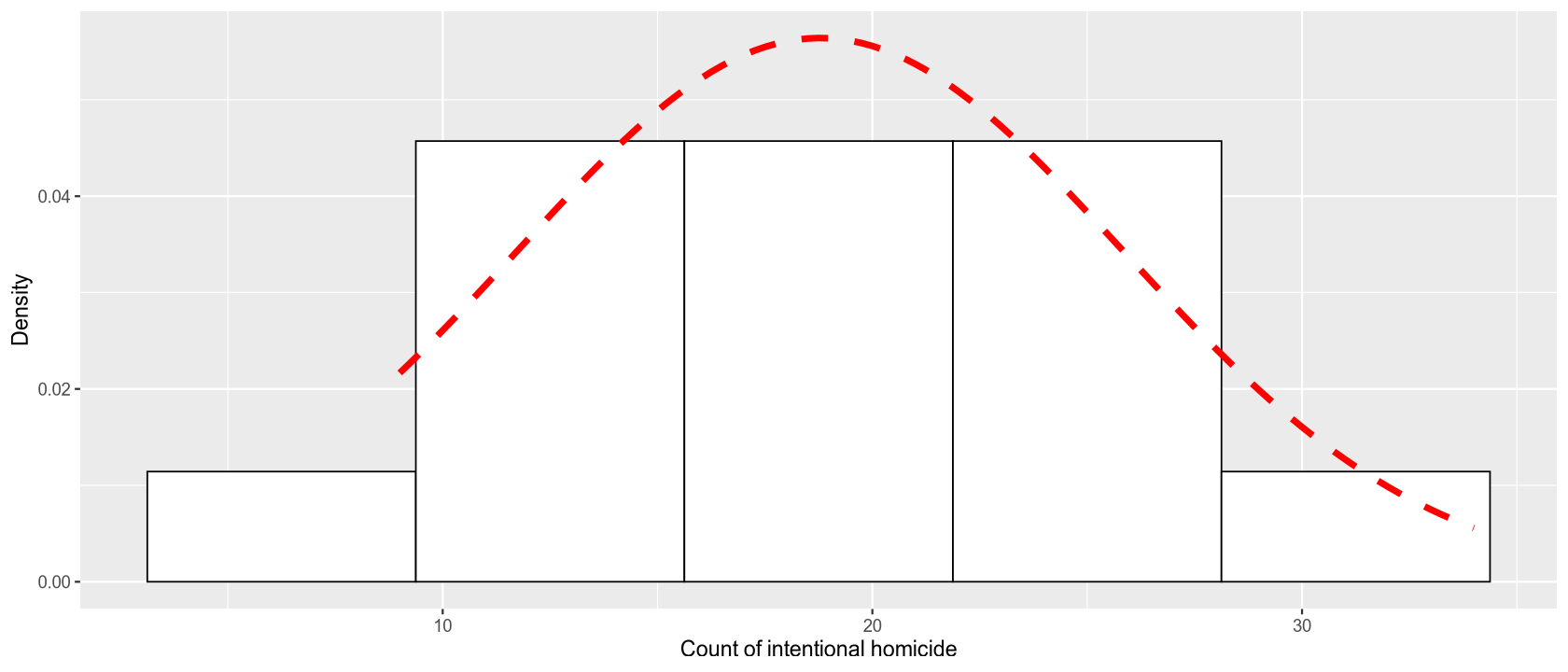

ggplot(cd, aes(x=values)) + xlab('Count of intentional homicide') + ylab('Density') +

geom_histogram(aes(y=after_stat(density)), colour = 1, fill = 'white', bins=5) +

stat_function(fun=dnorm,

args=list(mean=mean(cd$values), sd=sd(cd$values)),

colour='red', lwd=2, linetype='dashed')

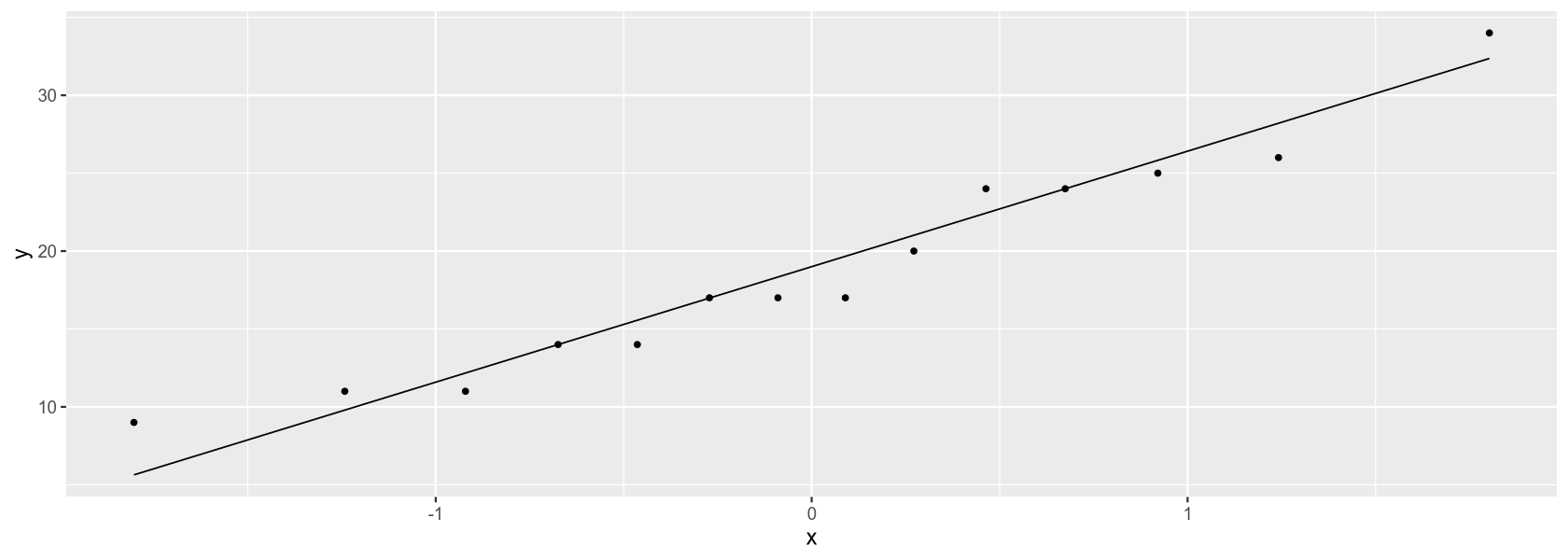

From the records of homicide frequencies in Vienna, we will test whether they come from a normal distribution. We will verify this hypothesis with a Shapiro-Wilk test and then compare the test’s conclusion with a Q-Q plot.

\(H_0\): The annual number of homicides in the Vienna region comes from a normal distribution.

\(H_A\): The annual number of homicides in the Vienna region does not come from a normal distribution.

shapiro.test(cd$values)

options(repr.plot.height=5)

ggplot(cd, aes(sample=values)) +

stat_qq(distribution=qnorm, show.legend=T) +

stat_qq_line(distribution=qnorm, show.legend=F)

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: cd$values

W = 0.94623, p-value = 0.5039

At a 5% significance level, we do not reject the null hypothesis that the frequencies of homicides in Vienna come from a normal distribution. This result is consistent with the Q-Q plot, where the records lie on the line without any obvious systematic under/overestimation.